Let's talk about negative practice. When talking about therapy for childhood apraxia of speech (CAS), you will frequently hear to avoid negative practice, but what is it, what should we be doing instead and is it ever okay?

What is Negative Practice?

Negative practice is when a child is practicing an incorrect motor plan. This means the child is attempting to say a word or phrase and they are saying it incorrectly. One of the principles of motor learning and neuroplasticity is that we learn what we practice. If a child is practicing saying a word or phrase incorrectly, then that is what they will learn.

<image idea – something showing a child practicing a skill OR something with a brain>

Unfortunately what I have seen occur at times in speech therapy is that the speech-language pathologist (SLP) is accidentally doing negative practice. Perhaps the speech target is too difficult for the child or the therapist isn’t sure how to provide additional cueing to help the child produce the correct production. As a result, the child’s practice during therapy is actually negative practice, as they are rehearsing an incorrect motor plan. Unfortunately, it’s often more difficult to change a learned motor plan than to learn a new one for children with apraxia, so now even more work and practice has to be done for the child to learn how to say the target word or phrase accurately.

As with many topics in speech-language pathology (and life!) there are lots of caveats and specifics that we have to consider. For example, the age of the child and the severity or significance of their motor speech challenges will impact how easy or challenging it is for the child to learn and change motor plans. We know that children who are typically developing speech will learn and produce word approximations that will then evolve into the adult version of the word/phrase as the child suppresses phonological patterns and acquires more advanced sounds. For children without motor speech challenges, this process occurs pretty seamlessly most of the time. A one year old may say “wawa” for water, then say something like “watah” then eventually produce the adult-version “water.”

Why can Negative Practice be Problematic?

For children with motor speech challenges, especially childhood apraxia of speech, their system is not as efficient and it can be much harder for them to change learned motor plans. For this reason, we want to be very careful about negative practice, including teaching and using word approximations, such as those that use phonological patterns and/or sound substitutions. In my experience, some very young children and those with mild apraxia are able to learn approximations and then change them later. In other cases, such as some older children and children with more significant motor planning/programming challenges, I have seen changing the word approximation that they learned to be a very difficult task.

If we are working with children that may struggle to change their motor plans such that we don’t want to teach approximations, what can we do instead?

How to Avoid Negative Practice

The first thing I suggest is to consider is the appropriateness of the targets (stimulability) and cueing. Hopefully the child’s speech targets have been selected based on stimulability during a dynamic motor speech exam. In a dynamic motor speech exam, the target words or phrases were elicited using multisensory cueing. However, I know sometimes the treating SLP is not the same SLP that conducted the evaluation and wrote the goals.

I generally follow the cueing hierarchy that is used in Dynamic Temporal and Tactile Cueing (DTTC). So at the start of a session or block of practice for a given word or phrase, I ask the child to say the target in imitation. If the child is not accurate then I would immediately add cueing for the next attempt. So maybe on the child’s next attempt I:

-

speak at a slower rate

-

ask the child to watch my mouth

-

use simultaneous speaking (where I say the target at the same time as the child)

-

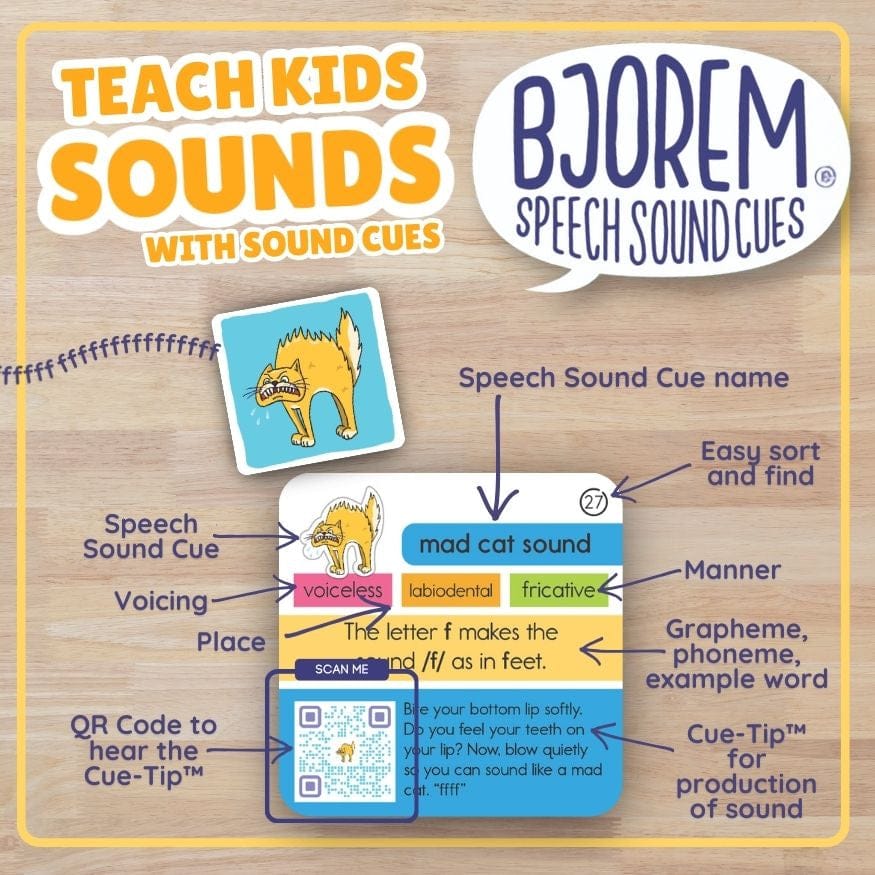

add a visual cue like Bjorem speech Sound Cues

-

add a gestural cue

-

add a tactile cue

-

all of the above!

All of these can be really helpful for helping to improve the accuracy and it might be the case that I am achieving successive approximations. Meaning that the child is becoming more accurate over a series of trials, even though they haven’t obtained full accuracy. The key is that they are getting closer to the correct production.

There's a lot of clinical judgment that comes into play as far as when to continue adding cueing and trying for the same target and when it becomes negative practice and you need to change gears. As long as the child is continuing to improve their production on most attempts and it’s moving in the right direction, I will continue to practice that target and possibly add more cues if appropriate. However, if the child's not responding to the cueing and they're not becoming more accurate, then my rule of thumb is I will discontinue that target after 3 to 5 incorrect productions. At that point I will switch to one of the child’s other targets.

Another situation that happens frequently is that children will be inconsistent, especially at the early stages of practicing a new target. Again, our goal is to be increasing accuracy overall and moving to a higher percent of attempts that are correct. If the child is inconsistent but is producing the target correct some of the time with cueing I will usually finish the block, which is often 10-20 trials of the target word or phrase.

If I do make the decision to switch targets, I’ll usually come back to the inaccurate target again later in the session and definitely at the next session. However, sometimes I find that there are multiple sessions in which the child is not able to produce the target correctly and/or is not increasing their accuracy (getting closer). In this case,

I usually put that target on the back burner for the time. I’ll periodically probe that target to see when the child might be more stimulable for it, at which time I will begin addressing it again.

Another very important part of this discussion is that by discontinuing when the target is not accurate, we are avoiding frustration. In my experience, children are often aware of whether or not they are producing the target correctly. If they aren’t and they know they aren’t, it can really hurt their trust in us as their therapist if we are accepting what they are saying as accurate or are not able to help them improve their accuracy.

What about Home Practice and Spontaneous Speech?

Another topic to consider with negative practice is parent education and home practice. I ask parents/caregivers to be present during my sessions and I am very transparent about what I'm doing with the child and why. I talk to parents about negative practice and why I might be changing a target or why I'm sticking with a target even though it's not completely accurate. Once I have explained negative practice, parents often become concerned about home practice or what the child is saying incorrectly outside of therapy.

One important aspect of this is that I don’t send a target home for home practice or homework until the child can do it accurately and independently at least some of the time and if they make a mistake, can correct it with a minimal cue such as someone modeling the correct production.

If a target is at an early stage in motor execution where I'm using multiple cues at one time, then I’m not going to ask the parent to practice that target at home YET. Often times in these early stages I am using a lot of my knowledge and skills and will be using simultaneous speaking, gestural cues, visual cues and/or tactile cues at the same time. I do not expect a parent to implement that at home. I will actually tell the parents NOT to practice that target at home and if the child tries it, to acknowledge their communication and praise their attempt but not try to correct it.

Once the child is more successful and consistent and I’ve faded cueing, then at that point I might ask the parents/caregivers to correct the child or ask for the child to correct their productions at home. I often give the family a couple of ways that they could help the child if the child tries it and isn't accurate. I encourage the parent to practice that target word or phrase at home in whatever natural context that word or phrase is appropriate. I also let the family know not to worry about negative practice in a child’s spontaneous or self-generated speech. We don't want to limit a child's language because of their speech and we can’t control what a child produces independently. So again, if a child is producing a target word or phrase that hasn’t yet been sent home for home practice, then I encourage the family to acknowledge the communication but don’t worry about a correction.

When Can Negative Practice Be Okay?

Let's talk about a time when you are not worried about negative practice and that's when you're doing Rapid Syllable Transition Treatment (ReST). ReST is an evidence-based treatment method based on the principles of motor learning that's shown to be effective for treating apraxia and dysarthria. It is known for using pseudo words, which are similar to real words but don’t have meaning. ReST consists of 12 sessions that are usually conducted 4x/week for 3 weeks or 2x/week for 6 weeks. For the 12 sessions, the SLP develops a list of 20 2, 3 or 4 syllable pseudowords that are practiced 5x each (100 trials) per session. During the practice portion of ReST sessions, which is the bulk of the time, the SLP only provides knowledge of results (whether the production is right or wrong, without any additional information) and fades this feedback from a high rate to a low rate during the session in order to encourage motor learning.

What this basically means is that negative practice will happen. The child will produce the pseudword incorrectly and the SLP does not provide correction or additional cueing to help the child correct the production. At the beginning of the next session the SLP can do a brief period of time in which they provide cueing, but for the majority of the session, this type of assistance is not provided. Hopefully over the course of the 12 sessions, the child’s accuracy on all of the psuedowords is improving; the ReST manual provides guidelines on accuracy and if the child’s accuracy is not improving, when to discontinue.

I have not had a child whose accuracy was this low but I have seen children who learned one of the pseudowords incorrectly and did not change it; the child effectively did negative practice of that pseudoword. But part of the beauty of using pseudowords is that there wasn’t a long-term negative impact because it wasn’t a real word. So after that block of ReST was complete, the child had no reason to use that pseudoword again. If the child does another block of ReST in the future, a different set of pseudowords will be used. Now obviously we don’t want most of the words to be incorrect, but that is why the ReST manual provides guidelines about when to discontinue and why there are guidelines on how to create the pseudowords so that the child is stimulable for them. It’s important to note that ReST has been shown to be effective for older children and children with mild to moderate apraxia; the child has to be able to make those corrections and improvements without cueing. If the child is able to do so, ReST can be a great way to improve the child’s motor planning and programming.

Summary

In summary, remember to be cautious about negative practice when working with children with speech sound disorders, especially children with childhood apraxia of speech. Negative practice can have its place in therapy, but make sure that you are not accidentally teaching incorrect motor plans that may have to be re-learned later. Instead, rely on multisensory cueing to help a child improve accuracy, and don’t be afraid to switch targets if a given target isn’t accurate at that time.